| |

Print

Sorrow and Strength -Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women

4-19-2017

We live in a connected world. Whether, through mainstream or social media, we receive a steady stream of news, much of it alarming. Examples of our inhumanity towards each other are broadcast widely with the freshest tragedy keeping the top spot for only a matter of days before a new atrocity takes its place. Each account is heartbreaking. We imagine ourselves in the place of the victim and their families. Cries of outrage become calls for peace. People, far and wide, encircle the survivors offering love and solidarity. Although the pain cannot be erased, at least there is a sense of fellowship, offers of aid, and attempts at comfort.

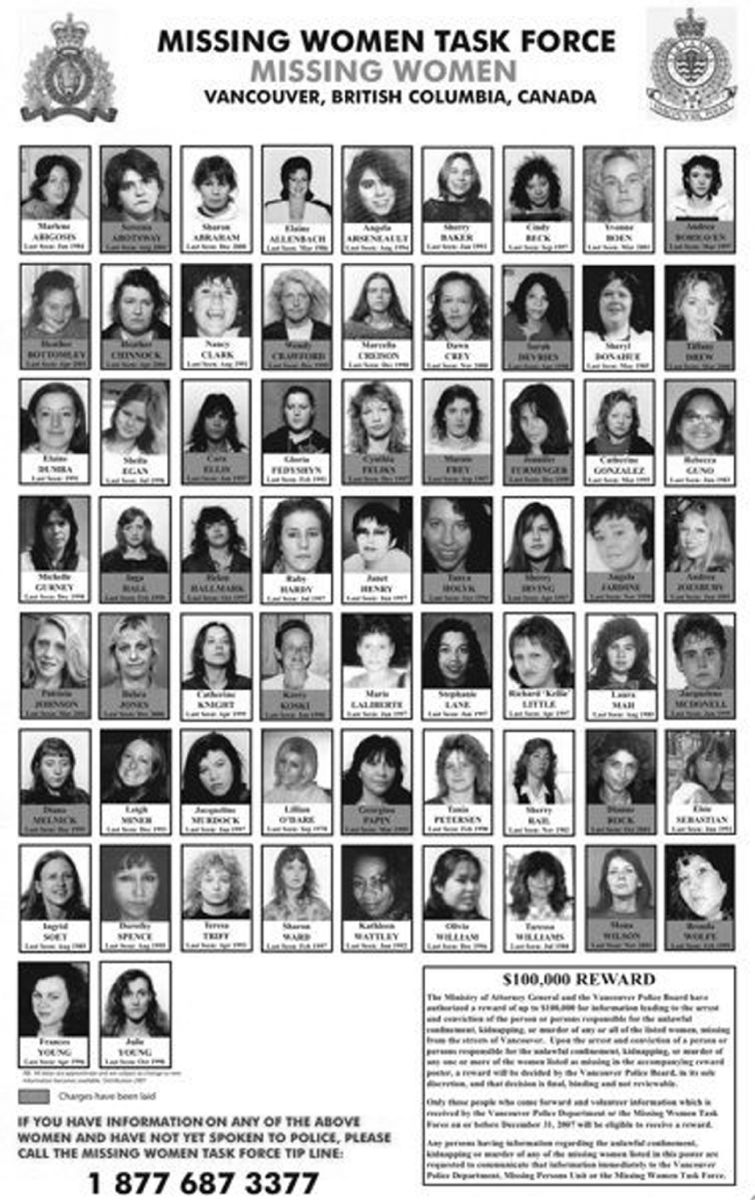

In the face of senseless violence, we draw together in a protective circle of strength. But here in Canada, the families and friends of the hundreds of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls are left wondering why there is an appalling lack of public outrage and so little support for them. Why are our hearts not breaking at their pain? Why is society so apathetic and even self-righteous about their plight? Why do we care about acts of brutality a world away, but turn aside from those targeted in our own country? Imagine the sleepless nights and distraught days you would suffer if your sister, aunt, or friend went missing with no clue of her whereabouts or well-being. Imagine burying your daughter, mother, or cousin knowing her last moments were filled with terror and pain. You would feel unbelievable sorrow deepened by society’s implied justification that she deserved her fate.

In 2004, Amnesty International investigated and released the scathing report “Stolen Sisters: A Human Rights Response to Violence and Discrimination against Indigenous Women in Canada” and yet very little action was taken. In 2014, the over 300 municipal and provincial policing agencies, along with the RCMP finally shared their files in order to get an accurate count – something they previously hadn’t bothered with. The report identified nearly 1,200 missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls between 1980-2012. Although Indigenous women and girls make up only 4% of Canada’s female population, they account for about 16% of female murder victims. The federal government is finally responding and has just launched an inquiry. Starting in May, a panel of commissioners will travel across the country to listen to the stories of the victims’ families and friends in order to make recommendations for change.

Their stories are hard to hear. Such as Beatrice Sinclair’s, a 65 year old grandmother, who was raped and between to death under a bridge in Winnipeg. Or Georgina Papin’s whose remains were found on serial killer Robert Pickton’s Port Coquitlam pig farm. Or Tamara Chipman who was last seen in 2005 along the “Highway of Tears”, a section of road running between Prince George and Prince Rupert.

None of these stories have happy endings. Maybe that is why we try to ignore them. We don’t want to admit that as a society we tacitly endorse ongoing and systematic poverty, addiction, racism, mental health stigmatism, abuse, and violence – as long as they don’t happen to us. They are somebody else’s problem – somebody else’s life choices. It’s their own fault they are in a bad situation. The stories from overseas are easier to handle. In them we can rally against a vilified enemy, we are the judge and jury doling out solutions to entrenched problems from the safety of our first world life. But when we face the crimes against Indigenous women and girls in our own country, if we are honest, we have to name ourselves as accomplices – an uncomfortable role to be sure. We each share the responsibility for what happens here at home. It’s time to reach out with empathy to the Indigenous community. To hear their stories. To share their anguish, but also to ignite hope. To be by their side in creating solutions that solve the underlying problems instead of ignoring them.

Each of the Indigenous women and girls who were murdered or are missing was loved by someone. They are still missed, mourned, and memorialized. But as Canadians, we haven’t yet responded with cries of outrage. We haven’t connected with the pain or drawn together in a protective circle of strength. It’s time we do so.

Zainab Dhanani can be reached at z_dhanani@yahoo.ca

Footnotes:

|